The term “eugenics” (from Greek, for “good birth or stock”) was coined in 1883 by the English naturalist Sir Francis Galton, with German economist Alfred Ploetz first employing the term’s German counterpart, “racial hygiene” (Rassenhygiene) in 1895. At the core of this movement’s belief system was the notion that human heredity was fixed and immutable, and that the social ills of modern society – criminality, mental illness, promiscuity, alcoholism, poverty – stemmed from hereditary factors (rather than environmental factors, such as the rapid industrialization and urbanization of late 19th century Europe and North America).

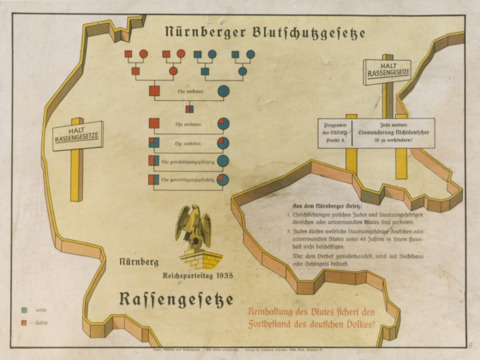

Nazi Germany’s racial policies, implemented with the assistance of medical professionals, targeted individuals defined as “hereditarily ill”: those with mental, physical, or social disabilities. Nazis believed these individuals placed both a genetic and a financial burden upon society and the state. One of the first eugenic measures they initiated was the 1933 Law for the Prevention of Offspring with Hereditary Diseases, which mandated forcible sterilization for those affected by nine disabilities and disorders, including schizophrenia and “hereditary feeblemindedness”. As a result of this law, 400,000 Germans were sterilized in Nazi Germany. Eugenic beliefs also shaped the 1935 Marital Hygiene Law which prohibited the marriage of persons with “diseased, inferior or dangerous genetic material” to “healthy” German “Aryans”.

Finally, the eugenic theory also provided the basis for the “euthanasia” (T4) programme – a clandestine initiative that targeted disabled patients living in institutions throughout the German Reich. An estimated 250,000 patients, the overwhelming majority of them Germans, were killed during this operation.